Here's How Not to Write About Slavery and the American Revolution

Joseph Ellis' new book purporting to confront "the downside of the founding" leaves much to be desired.

The United States is gearing up for the celebration—if that’s the right word—of the country’s 250th birthday next year, and already there has been a noticeable rise in the number of books, documentaries, museum exhibits, and other cultural products that promise to take some new, unappreciated approach toward the much-studied events that culminated with the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. Some of these works are phenomenal. The next episode of THINK BACK, which I am currently editing and will release next week, discusses a new book that manages to break significant new ground on the topic.

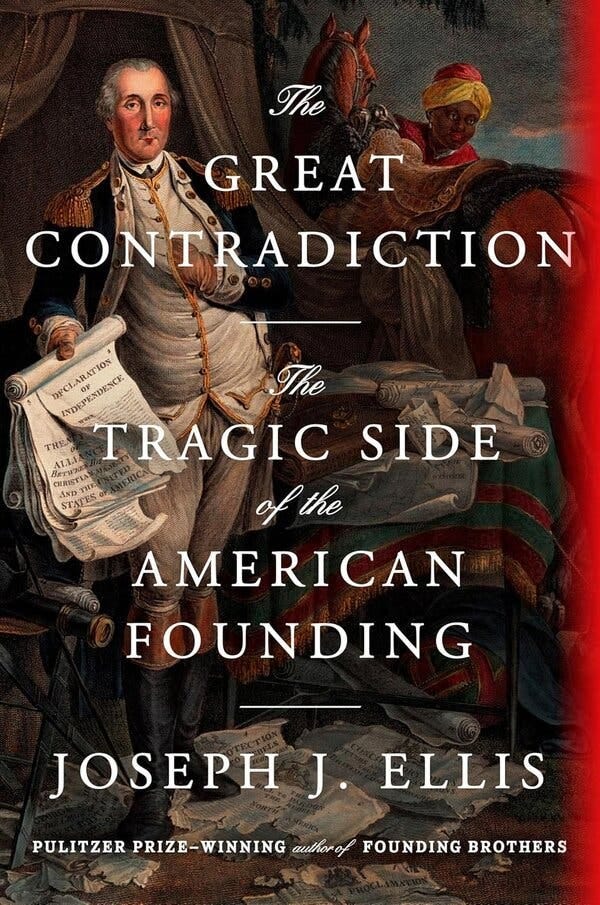

Others are less original—and less convincing. Unfortunately, I found that to be the case with the historian Joseph J. Ellis’ latest, The Great Contradiction: The Tragic Side of the American Founding. The New York Times Book Review asked me to write about the book—an immense honor—and my review was published last Tuesday. Here’s a taste:

Straining to hold their ideals and practices in uneasy balance, the founders contorted themselves in absurd ways. James Madison, adept at what Ellis calls “enlightened obfuscation,” might start a sentence by criticizing slavery but end it by hiding behind “a verbal fog bank that descends over the entire subject like a cloud.” In 1790, Madison called slavery “a moral and political evil” but deemed it “improper” to push for abolition at that moment. The right one never came, though he lived another 46 years.

Early on, Ellis unhelpfully describes today’s roiling debate over the founding as occurring between “pro-American” and “anti-American” factions. “Both sides think more like lawyers than historians,” he writes. But in “The Great Contradiction” he, too, seems to approach the work as an attorney — defense counsel in a capital trial who raises every mitigating circumstance he can think of to keep his clients out of the electric chair.

It goes on from there. Generally, I found the book regrettably thin. As in earlier works, over and over again, Ellis presents himself as charting a lonely path between “mindlessly celebratory and naively judgmental” takes on the founding. But what he frames as bold truth-telling has been offered many times before, often with more original research, richer storytelling, and subtler analysis. While adding little to what often already feels like a fairly exhausted debate, Ellis repeatedly castigates unnamed fellow historians for pursuing a “moralistic agenda” and engaging in “presentism”—the practice of judging people from the past by today’s ethical standards (a sin he likens at one point, rather offensively, to slavery itself).

Ellis’ own work shows that we don’t need to adopt present-day views to condemn eighteenth-century slavery. “I will not, I cannot justify it,” he quotes Patrick Henry admitting. A Pennsylvania congressman said he was astonished, in 1790, to hear somebody defend slavery “at this stage of the world.” Clobbering his straw-man to smithereens, Ellis dismisses scholarship with which he appears to be only passingly familiar. Tellingly, he keeps slavery and Native removal in separate silos, when the best recent work depicts them as twin engines of a single continent-conquering project.

I also feel that Ellis misunderstands the stakes of the debate in which he claims to heroically intervene. The real argument is not whether the founders might have abolished slavery—as Ellis rightly concludes, they almost certainly could not have—but whether we today should remain bound by the bargains they struck. To note that a truly antislavery constitution (not to mention a more democratic one) could never have been ratified is no defense of the one we’ve inherited. It is, rather, an argument for why it deserves less worshipful scrutiny.

Perhaps the thing I found most disappointing about the book was how recycled it feels. Obviously, somebody who has won a Pulitzer (for American Sphinx, his biography of Thomas Jefferson, back in 1996), somebody who has sold gazillions of copies of books—and done a real service making American history enjoyable and accessible for millions of Americans—has a certain license to take their foot off the pedal at some point. But Ellis’ dismissiveness toward other historians, mentioned above, strikes me as making the significant flaws of his own late work fair game for critique.

The endnotes to The Great Contradiction are littered with citations to Ellis’ earlier books, which he does, to be fair, acknowledge relying on “heavily.”

Perhaps more heavily than is really kosher. He writes at one point that history is all about leaders “improvising on the edge of catastrophe”—a phrase I underlined as a nice turn of phrase, until I realized that he also used it in both American Creation (2007) and Revolutionary Summer (2014), and appears in any case to have borrowed, uncredited, from Arthur Schlesinger Jr.

I didn’t end up including this paragraph in my review—seemed a little too ad-hominem-y—but here is how I originally intended to conclude the piece:

Ellis often urges readers to adopt a “higher altitude” perspective, and indeed he tells us he wrote the book from his “mountaintop study” in Vermont. The image is telling, evoking both Jefferson’s Monticello and the granite faces on Mount Rushmore, lofty monuments to men whose compromises and contradictions continue to shape American life. But the view from above, however “panoramic,” as Ellis likes to put it, can blur lived realities on the ground. Ellis is at times guilty of what he accuses Jefferson of—“avoiding any subject that roamed too far from his elevated and often visionary comfort zone.” Ellis’s work has long suggested we look to the founders for guidance. Perhaps, after a quarter of a millennium, it is time to look elsewhere.

You can read the review here. It should be out in the print edition in a few weeks.

Meanwhile, look out for the next podcast episode, with a guest who shows there is still important and fresh work being done to understand the Revolution in all its world-spanning origins, entanglements, and ramifications.